Game Seven

Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying About Scoring in the Most Important Game of My Life

Can you imagine going from the best play of your career in Game Six to scoring zero points in Game Seven? Well, I don’t have to imagine it. Neither does Ray Allen. Because after our historic victory, we went cold. Ice cold. Tundra cold. March of the Penguins cold. And in the most important game of our careers, between us, we didn’t score a single point. Goose egg. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

Thankfully, Bron and D had our backs. I remember walking out of the tunnel before the game with D in my ear, hyping me up: “This is our championship. Let’s get it.” From the tip, Bron and him played with exactly that attitude, dominating the Spurs from the jump. Meanwhile, I was looking for a rhythm of my own, but things just weren’t snapping into place.

Remember everything I said about Timmy D? My defense was tight, but he still made it feel like I was doing everything wrong. He was teaching post mastery—and I happened to be the night’s subject.

I wasn’t finding much luck with the ball, either. My shooting hadn’t been strong the whole series, and it didn’t seem like it was going to suddenly turn around. Things came to a head midway through the third quarter. We were tied at 54, and D had the ball near the sideline with Tony Parker tight on him. I ran down to set a pick even though I heard him telling me not to come, and he ended up being right: There wasn’t enough space, I ran straight into the pick, and when the ball ended up out of bounds, D voiced his displeasure with me. I fucked that up, I thought, running back to face Duncan again. I was blindly putting myself in the middle of the action, not looking for the best ways to help us win.

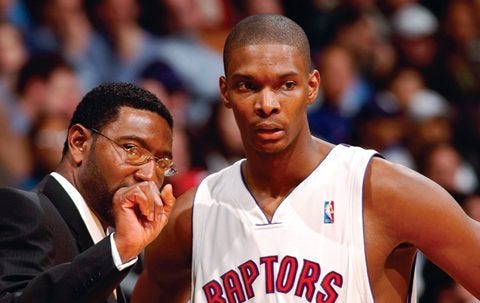

That’s when my own voice in my head gave way that of someone else: Sam Mitchell, the veteran small forward and coach I’d been lucky to play for in Toronto. We were on the road sometime in 2007—in San Antonio, of all places—and I was deep in a funk, so he benched me. I thought it was because I wasn’t scoring, but the minute I sat down he gave me an earful right there in front of everyone, and I realized it was because of everything else I wasn’t doing. “It’s unacceptable to be the best player on the court with the ball in your hands and suddenly not be without,” he said. “Defense and rebounding has nothing to do with talent, just perseverance and determination.”

We ended up winning that game with me on the bench.

He reminded me of something I knew, but still managed to forget often as a young player: Even when you’re not getting your points in, you have to contribute.

I needed to hear it back then, and I certainly needed to remember it six years later during Game Seven. As I walked to the bench, I thought of Sam telling me how many other facets there are to the game. I realized I wasn’t going to score at all that night. So I called up my mental checklist: defense, rebounds, assists. It was like retaking a test—only this time, I wasn’t fixated on acing it by scoring big and thinking of myself or my stats. I just needed to find the best way to make sure our team won.

Clocking back in with seven minutes left, I focused on rebounding on both sides of the court. When I could, I’d try to move the ball around to the guys who were still cooking—not only Bron and D, but on this night, Shane Battier too.

My man drained 6 threes in Game Seven, after struggling to connect for a lot of the playoffs. Later, I asked him: “How’d you hit those shots?!”

“I kept missing to the right,” he told me, “so I just aimed for a different part of the rim.” Two minutes after he checked into the game, he nailed his first of the night. And then they just kept dropping.

Anyone who says the Hot Hand is a fallacy isn’t a scorer; Shane that night was proof that drilling one shot absolutely puts you in a better place to make the next. Same goes for the opposite: I could not buy a basket from the start of that game, and unlike Shane, I didn’t have a tactical fix. So it stayed that way.

Being a natural scorer, it was hard not to freak out as the time continued to tick in a Game 7. But everyone else did their part to carry us—and then, we were in a position to win.

I still remember the moment it felt real. We were up by four when Tim and Manu ran a pick and roll on Bron and me. I don’t know if he heard me, but I screamed as loud as I could for Bron to switch, before he read the pass Manu was throwing perfectly, stole the ball, got fouled, and went to the free throw line.

Functionally, it was game over.

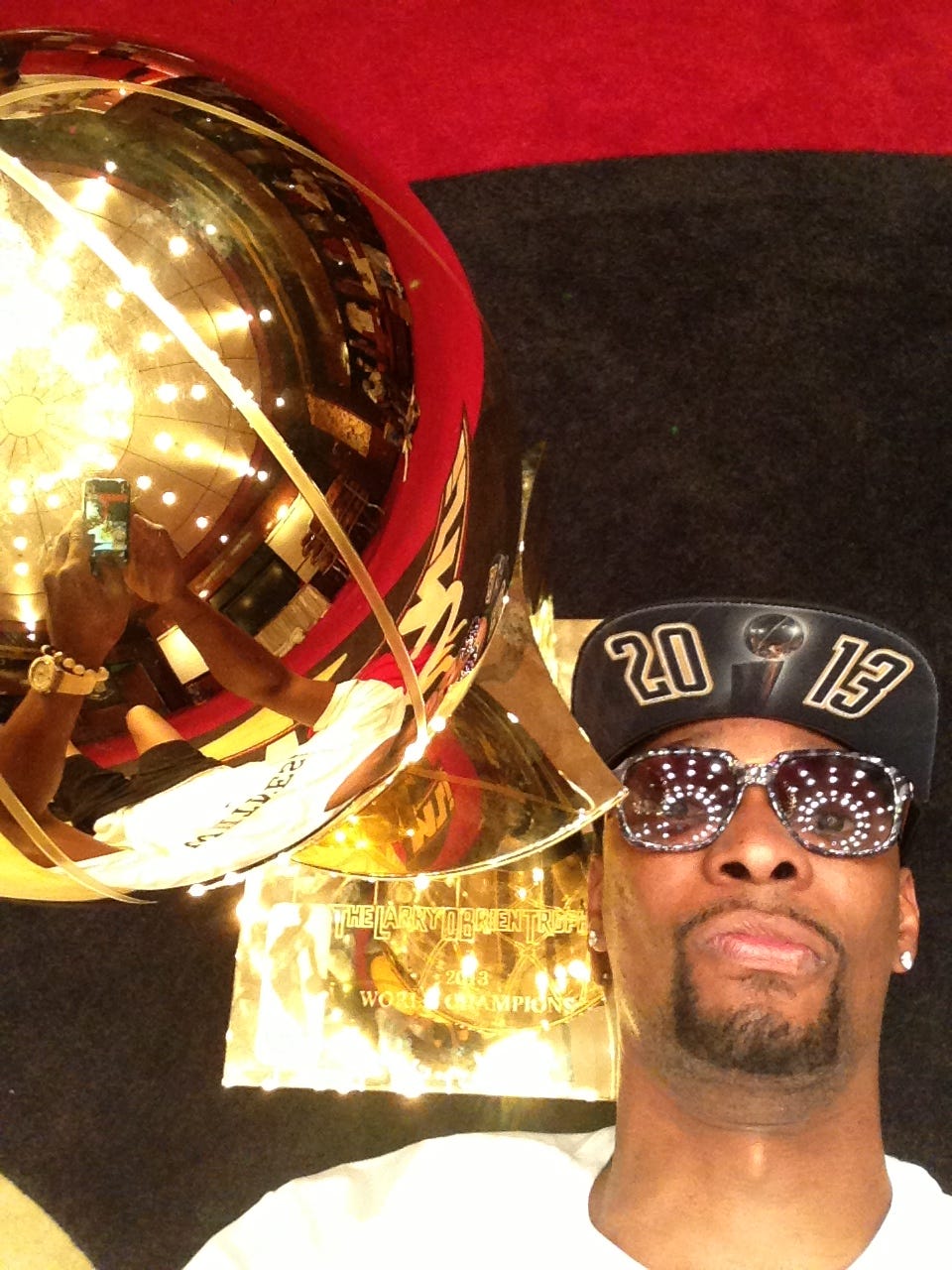

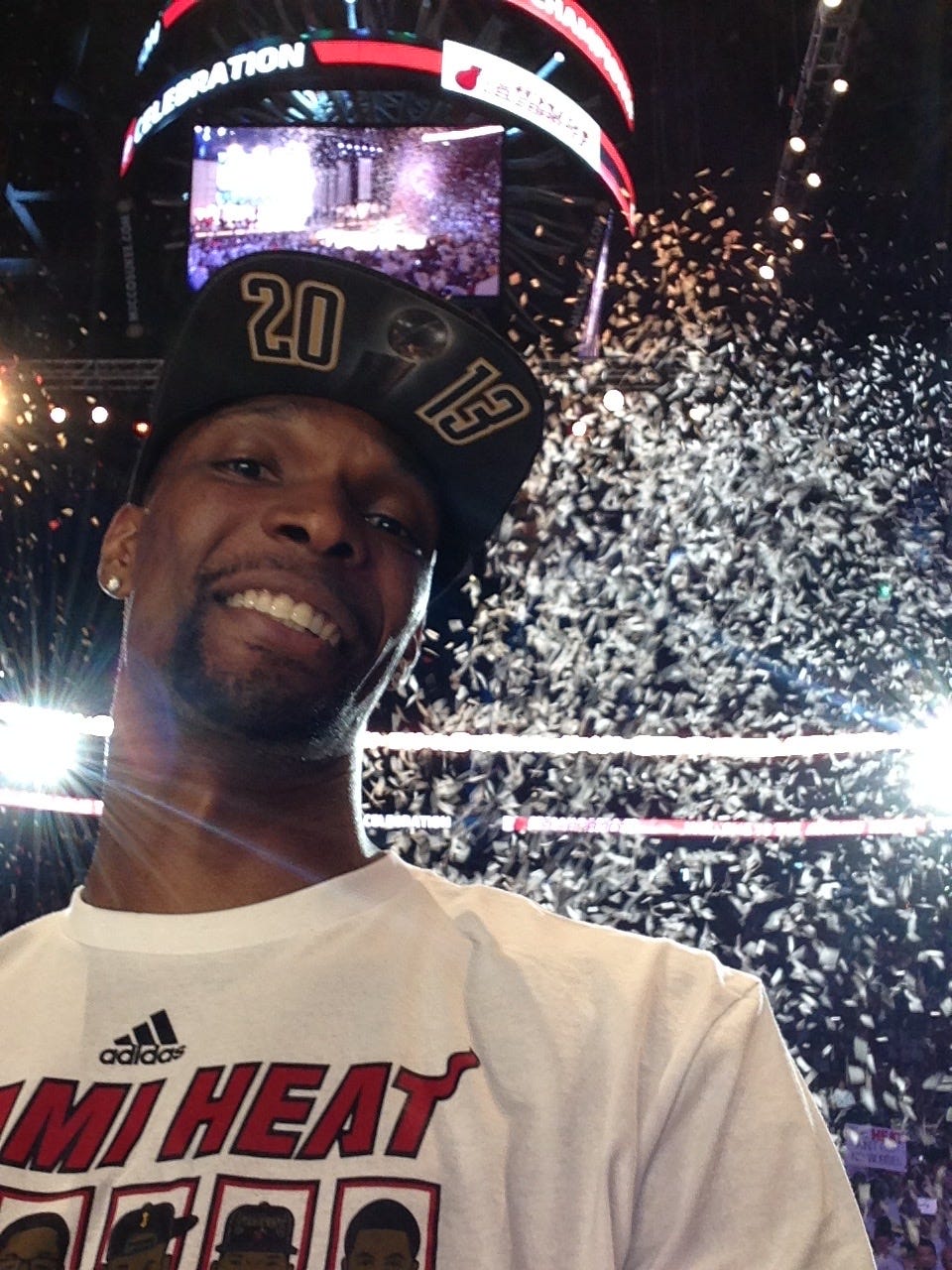

There was no last-second drama, no moment when we had to worry after that; in a strange way, things felt calm. A few minutes later, I took a pass from Rio and sent it back to him as the whistle blew. Fans cheering. Confetti falling. The championship trophy rolled out; this time, for us.

Everyone on the bench was hype, but looking around at the guys on the court, we all shared the same mix of exhaustion and relief, a version of the same thought in all of our heads: Oh my god, we actually won that?

I hope I don’t catch too much heat for saying this: I thought winning that series would be way more fun than it actually felt. When you’re fantasizing about the finals as a kid, you’re thinking about being The Guy—the reason the team wins. You’re thinking about having limitless energy to mob your teammates the minute the clock runs out. You’re not thinking about trying to do whatever you can to win, even if that means putting up zero points on Game Seven.

I truly can’t express quite how wiped out we felt by the end of the series. It was like my body instantly remembered how many games I’d just forced it to play. Even though Game Six was our big comeback, I’d say Seven was even more grueling.

Suddenly, I was crying again—not tears of sorrow but tears of joy. And now, I was cool with it being on national television.

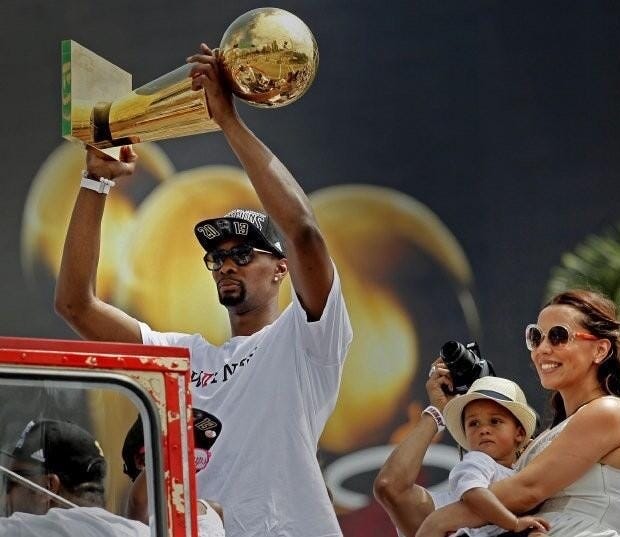

Remember when I told you about trying to pick up my kids after we beat Indiana? Next thing I knew, they were swarming me again, asking to be lifted once again as the team took the stage to get our trophy. My son was barely one—he’d just started walking—but he could tell this was something he wanted to be a part of. Around then, the relief became euphoria, and it didn’t go away for hours.

When we finally left the stadium at three in the morning, even the people celebrating outside had already gone home. But as I’d soon learn, our night was just starting.

Back at home a couple hours later, I was zoning out and winding down while listening to YEEZUS — it had just come out — when I heard Adrienne’s voice: “Honey, you have to go to the party.” I knew better than to do anything but get dressed. We spent the rest of the morning at Story. I wish I could remember anything substantial from that club. Bron, D and I were in a packed table section and Drake was there hanging out too—that much I can tell you.

After the afterparty, D and I hung out at my place, shooting the shit until the sun rose. We talked a bit about the season, but mostly we were just decompressing, enjoying the fact that we’d just won a championship and didn’t have to worry, at least for the night, about how we were going to win another one.

At one point, D noticed a prized possession of mine on the wall: a signed lithograph of some NBA greats, one of the first things I’d bought as a rookie. As we appreciated MJ’s signature—which was great because of course it was—I thought about how far that piece of memorabilia had come with me: from Toronto to Miami, from championship to championship, as I grew as a player and as a person. And I thought about everyone who came before us, from Jordan to Kareem to Russell, who paved the way.

I had the same thoughts three days later, as our parade made its way through downtown Miami, fans lining Biscayne Boulevard to get a glimpse of us. It was hot, and loud, and there was no way I was going to put down the trophy. I’d been so caught up in the same wildness the year before that I hadn’t really gotten much time with the gold, but now, with my hands on it, it felt like mine in a way it hadn’t before. I still don’t quite have words for what that day was like.

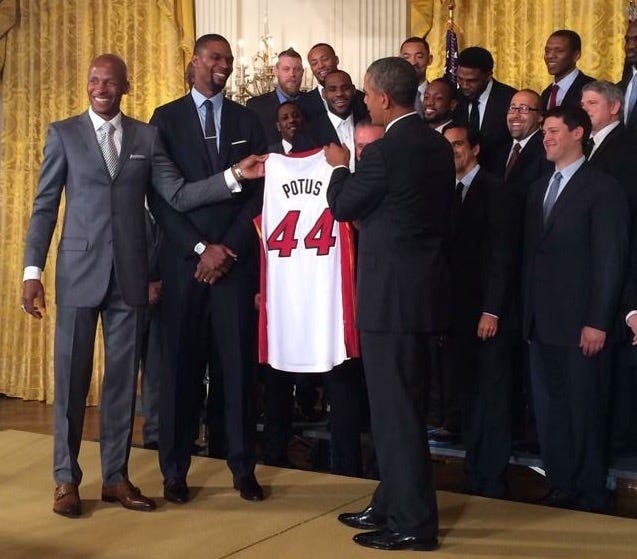

Most people think you’re free of obligations as soon as the Finals are over, but the days between the last game and the parade are still team days. That means team meals, and, yeah, a few more team parties. I’m not complaining about any of that—and the big dinner that happens after a championship, with everyone from the Heat family and their family? That’s tremendous.

But the minute that parade is over, it’s like the last day of school: Everyone’s instantly on vacation. Adrienne and I took the kids to Italy. I spent the first week of the trip doing close to nothing, savoring every second of that time with my wife and kids. And I let the realization that we’d won again—that we’d done exactly what we set out to do—wash back over me every day.

You’re playing yourself if you think that’s how I spent the whole summer. Around the second week, I found my way to a stationary bike and began to do some ab workouts. It wasn’t the most intense stuff, but it’s what I needed at the moment: a toe-dip, a way to ease back in toward testing myself once again, always working not just to maintain, but to get better.

I knew every other one of the guys would be starting to do their own version of the same: getting their reps in; working what needed to be worked; gradually ramping it up as the season went from two months away to one, then to weeks, then to days.

We’d done it again—no one could deny it, and we certainly weren’t going to forget it. But we were sure as hell going to use it to come back just as hard in the fall. Because, I’ll be real with you: You never think it’s going to be The Last Chip.

Thank you for joining me in reliving the craziest series of my life — and some of the most memorable moments from our final championship season. There’s more to come, so if you’re not already subscribed, you can do that below. Talk soon.