Why I Write

If I told you a rapper and a ritual got me thinking about writing a book, would you believe me?

When people ask me how I ended up writing Letters to a Young Athlete, I can’t imagine they’re expecting to hear it started with a book recommendation from J-Cole. But what can I tell you?

This was a couple years after I retired. To be honest, at that point, I didn’t really know what I should be doing with my time. My whole life, I had dreamed of following my heroes—not only to the NBA, but to a career that went deep into my thirties. I wanted at least twenty thousand points and ten thousand rebounds. I wanted championships—which I got—but once I did, I wanted more. And then, suddenly, the future I’d dreamed up for myself, and spent tens of thousands of hours working toward, was out of my reach.

When doctors looked me in the eye and told me I’d never play in an NBA game again, I didn’t want to believe them. For a while, I didn’t, until it became clear that if I didn’t follow their advice, I could end up losing my life.

I’ll be straight with you: If I were on my own, I might have tried to risk it anyway—if a team would’ve signed me. But I had a wife and kids, who I loved even more than basketball, which left me with no choice but to retire.

Still, that didn’t mean I had any clue what I should do next. That’s the mindset I was in on a trip to San Antonio, where my buddy J-Cole was performing.

When the two of us spoke backstage at his concert, I wanted to talk about anything but basketball. The pain from ending my career was still too raw. So I asked him what he was reading. He told me he was knee-deep in a book called The Artist’s Way, by Julia Cameron.

A few days later, I was reading it too, and following Cameron’s advice to start writing “morning pages”: three long-hand pages every morning, with no judgments or thoughts outside the ones you’re putting down on paper. The goal is to empty your mind, and that’s exactly what I found myself doing—until, eventually, my mind was filled with a thought I’d never considered before:

I should be writing.

Like, professionally.

On the one hand, this was a crazy idea—I’d never written anything seriously before. But, on the other hand, I had always loved to write.

As a kid, whether I was taking notes or taking stock of my own feelings, I’d write out my thoughts on whatever was handy: computers, notebooks, the backs of napkins, my own hands. In the NBA, I didn’t have much time to practice the hobby, but retirement gave me a chance to find my voice again.

And morning pages gave me a chance to figure out what I was really thinking about—what was really animating me—underneath all the noise that occupied my brain during the rest of the day.

Before I knew it, I started to have a better grasp on my feelings—not just my present, post-retirement ones, but across my entire life, right back to the days of pickup games with my friends on the concrete in Hutchins, Texas.

Basketball, I came to realize, was always my life. I hadn’t ever really given that much thought, because it was just true. Once I started writing about my early years, though, I drilled down on what had drawn me to the game in the first place. Returning to the living room of my childhood, I wrote about the familiar sight of my Dad, who I looked up to in every possible way, huddled around the TV with his friends. I wrote about what they were watching—basketball, of course. And I wrote about why their love for the game soon became mine: seeing people who look like you being successful, athletic—shit, being cool—is one of the most powerful experiences you can have as a young person. And it was particularly powerful to me, as a Black boy who didn’t always see myself reflected back on that TV screen.

I’d sit up at night watching every college tournament from the Great Alaska Shootout to the Maui invitational, trying to draw the plays I saw executed by kids ten years older than me. I obsessed over cards and sneakers, even when we didn’t have the money to buy them. And even then, when I’d run into constraints that often prevent kids from thinking their hopes can become realities, my dream only got stronger.

I came to love the idea of working towards it—of striving. I had the blueprint, one I’d inherited from the players I looked up to, and refined for my own self.

My version of the blueprint had a unique shape: growing up, I had one foot planted with the cool kids and one with the so-called “geeks.” Basketball became the bridge between those two worlds. In time, it also helped connect my love for sports and competition to a family tradition that went back further than anyone in my household: education. My grandfather, Daddy Jack Bosh, made sure all of his children were educated wherever possible—and in the Jim Crow south, that wasn’t easy. So when I realized my dream to play ACC ball, it wasn’t only about the game. A college education and a starting spot for the Yellow Jackets were equally important opportunities, and I made sure they were always feeding, and not fighting, each other. It was a natural fit—because in the classroom and on the court, I was doing the same thing, that core impulse I’d come to love so much: I was working hard. And in that work, I was finding joy.

That’s why I wrote this book, I’ve realized: to tell young people that being an athlete isn’t about the medals and trophies, as cool as they are. It’s not even about making the league—because not everyone does. It’s about finding something you connect with, something that connects you to others, and dedicating yourself to it. Doesn’t have to be a sport. Could be an art. A person. A role within your own family. You could dedicate yourself to writing, and start by doing morning pages.

In fact, that’s how I finally answered the question of how I ended up writing this book—with an assist from J-Cole. Unlike basketball, I wasn’t driven by a dream of becoming an author from the jump. Writing was something I started doing to fill the brown, leather hole in my heart. Dedicating myself to it was a practice, and a difficult one at that—as anything worth doing is. But somewhere along the way, I realized I had something to say. So I went ahead and wrote a whole damn book.

I didn’t think about why I was doing it, probably because the answer was so deep in my bones. But when it came time to put it into words, I knew exactly what to do: I just sat down and started writing. Word after word after word. Count it up, count it up, count it up, count it.

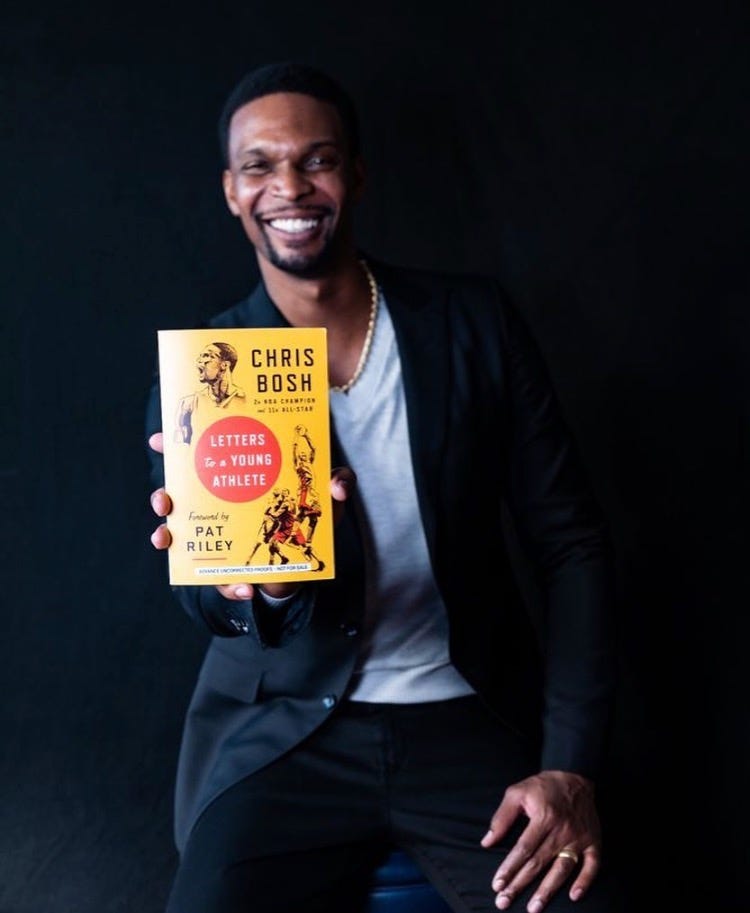

My book, Letters To A Young Athlete, is finally out—and you can order it pretty much anywhere. I’ve poured my all into this thing, and can’t begin to tell you what it’s meant to hear from readers far and wide as they discover the book. I can’t wait for you to read it, and hope you’ll tell me what you think.