Welcome back to The Last Chip, the newsletter where I share stories and lessons from behind the scenes of The Big Three’s last championship season. This is a free post, but if you want access to every issue of The Last Chip—and if you want the chance to talk with me directly in the comments—you should become a paid subscriber.

All proceeds from the first month will be donated to Color of Change, a leading organization in the Black Lives Matter movement, and all it costs is five bucks, so sign up now:

The Finals always goes smoother when you’re planning them in your head. Before we even played a second of basketball against the Spurs in 2013, we assumed we’d pull out to an early lead in the series—2-0, maybe, nothing crazy. You visualize like that not only because you want to, but also because you need to; because entering the Finals with any other expectation isn’t helpful. From the beginning of the season, we had seen ourselves holding that trophy, hugging each other, blanketed by sticky champagne and confetti.

Of course, things didn’t quite happen like that. From the first game, our back was pushed so tight against the wall that we didn’t have time for any emotions, even when we won.

Heading into the fourth game, we were in a position you don’t ever let yourself think about: being down 2-1, playing one of the best teams of all time in the middle of their homecourt stretch. If we lost, it wasn’t “over”… but it was baaaaasically over. It’s the sort of turning point that entire seasons—entire careers—lead up to.

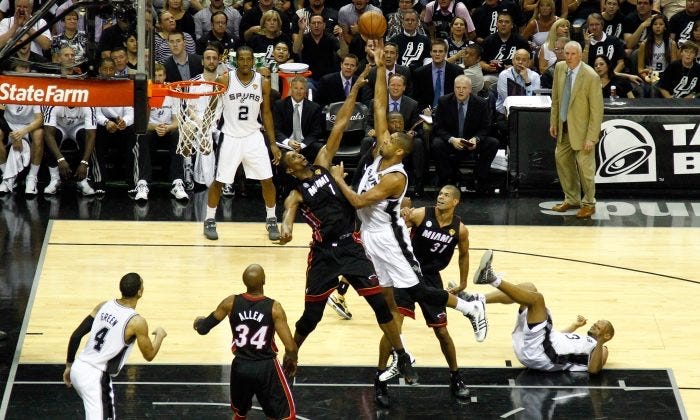

So I could talk about a lot from Game Four: how we played like our asses were on the line and then some, outscoring them in three quarters. I could talk about the way our defense and offense meshed, turning turnovers into opportunities. I could talk about Bron’s domination in the first half, sinking almost every shot until D carried our momentum forward. I could talk about me, too—running it with those guys when we were all on the court, and shouldering the momentum while they rested. How combining for 85 points and 30 rebounds wasn’t as crazy as it sounded—it felt natural.

But what I really want to talk about happened after that game, once we’d made it clear that we weren’t going down easy. As everyone celebrated the W, we hugged each other. And, for some reason, it was emotional. We weren’t wearing champions shirts yet, and instead of bubbly and confetti, there was only sweat, but this wasn’t a celebration, anyway. It was relief. This was the first game of the series where we all clicked, individually and as a collective, on the road. In moments like that, we felt like we were living up to the expectations that came with being the Big Three. It was about the game, sure, and the whole series. But here’s something else you should know: We’d been through a lot together.

When I first met him, “LeBron James” was a name, not a face. The year was 2001, we were at ABCD camp in Teaneck, New Jersey, and the internet wasn’t the Internet yet, at least not where I was from. So the articles everyone was reading from their dial-up modems didn’t have pictures.

I read all of them, heard about this kid out of Akron who was turning everyone’s head. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a little tight about it, too – I was 17, and thought I was pretty damn good myself. Then I saw him play. There’s a difference between being a teenager with game and a teenager with pro game. That was Bron. Everything I could do, everything I thought set me apart, he could do, too. We played each other a handful of times that summer, at camps and in tournaments across the country. But we never spoke—you don’t always talk to kids on the other team. I was introverted, too, focused on the fundamentals and little else.

Two years later, I met D at a Dave and Busters. We were at a pre-draft camp for college players, and shared an agent. I hadn’t known him at the beginning of the season, but by the end of March Madness, when he put up a triple-double for Marquette against Kentucky, I was asking the same question everyone had about Bron: Who is this guy?

We were all just kids, trying to deal with the feelings that came with our age—competition, self-consciousness—in some truly unreal situations. Getting to know somebody at that age isn’t always easy. It’s certainly harder when you’re trying to beat them all the time.

All that only intensified once we got to the league. It was impossible not to compare myself to the guys—Bron, D, Melo—from my draft class, while we were competing for all-star selections and postseason glory. And things got really interesting when we started playing together. The summer after D, Bron and I played the All-Star Game in Houston, we were in Japan for the 2006 FIBA World Championship, along with Melo, Dwight, Chris Paul, and a bunch of other ringers. Two years later, we had each carved out a place in the NBA. We were repeating as All-Stars. And we were headed for Beijing.

That’s where we really became friends: The Olympics. By then, we’d played against and with each other long enough to have some sort of rhythm. Like any old friend from somewhere else, you get used to picking up conversations where you left them the last time you hung out. We played cards, got food, out in the hotel. We also won gold. I know people like to say that’s where we started talking about becoming the Big Three. That’s a fun story, but the truth is, when I got back from China, I wasn’t thinking about forming a superteam. None of us were. We were each trying to win. In a way, it was the same dynamic we’d started with at the beginning of the decade—we were just better friends now.

That connection was crucial when we faced our first big disappointment together. I’ve already talked plenty about that first year—learning to play with each other while tuning out all the noise from off the court. But I haven’t mentioned what happened at the end of that season. I’m talking about the Mavs. Getting beat by them.

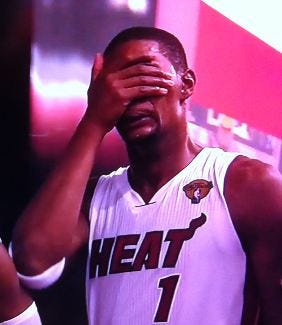

Like I said, you never plan to lose, but that year, we hadn’t even let the thought cross our mind. We were thinking of ourselves like the Mighty Ducks—The Team, emphasis on the capital Ts. Problem was, Dallas had a Team, too. Watching Dirk and Jason Kidd celebrate with Coach Carlisle, we didn’t even feel like anything had been stolen from us. Mostly, we were sad. Despite the cameras, I couldn’t help but feel everything right there on the court—the weight of trying to control the uncontrollable. I cried on national television. And I was so upset about losing the series, the embarrassment of my weepy face on T.V. barely even registered.

All season, we’d been trying to ignore the people rooting for us to fail. But we’d given them exactly what they wanted, and it was devastating. On top of that, the lockout was on the horizon, so we didn't know when we’d play again. For the first time in years, the three of us started to drift a bit. For weeks at a time, we weren’t seeing each other, or even exchanging texts.

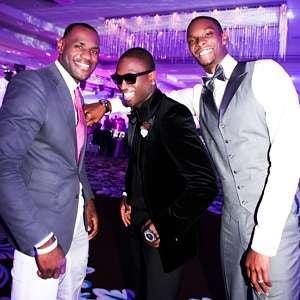

I couldn’t stay in that rut, though, because I was getting married in July. Dirk had already ruined my season. I couldn’t let him ruin my wedding, too. On the day, Bron and D showed up, dancing and laughing. Seeing them there, catching up on what they’d been up to while getting to celebrate one of the happiest days of my life—it turned things around, reminded me that we hadn’t joined up to play just one season. We had a lot more work to do.

A few weeks later, Adrienne and I were on our honeymoon in Saint-Tropez when we ran into Tyson Chandler at lunch. Of course, I had last seen him when we shook hands after the finals. “Don’t worry about this one, man,” he’d said. “You’ll win.” Even so, the thought of going over to his table now was crushing. Every competitive bone I had was telling me to stay put, stay hurt, dragging me back to the bitterness I thought I’d gotten over after the wedding. But Adrienne made me confront him, and I’m glad she did—Tyson’s a total nightmare to play against, a fierce and physical leader. He’s also one of the best friends I had from the league. And I knew he’d been right—we were going to win. The only question was going to be how many.

That determination carried me through the next season, and the 2012 chip, and straight on into the next. But hugging Bron and D after Game Four, I wasn’t even thinking about winning. I was focused on survival—that we’d fought our way to a win on the road, and now things were even. Deeper than that was something I’d known since we were teenagers: That these were two of the most tenacious guys you could ever hope to have on your end of the court. All the time we’d had together, playing in youth leagues and on foreign soil before ending up in Florida, had led to this.

You could argue that we shouldn’t have put so much weight on game four, because the next time we played, the Spurs came out blazing. We weren’t slouching, but their whole team had a special relationship to the net that night. For every rebound I grabbed, it felt like they were putting five shots up—and all of them were dropping. At the same time, I’m glad we got that moment of pride before a loss like Game Five. We were dealing with a familiar feeling—this wasn’t supposed to go like this. But that very thought—that we’d already been in a corner, and pushed our way out—left us knowing there was really only one thing left to do, something each of us had done countless times our entire career: go home and regroup.

Getting to return to Miami was a blessing and yet another reminder: This one of why we’d worked so hard for our home court advantage. Because beating us in San Antonio is one thing. But if you wanted to beat us in our house, you were going to need to bring it. And I’ll be honest: After everything D, Bron, and I had gone through together, we had no intention of letting our story end in Game Six—or with another photo of me in tears.

But boy, was it close.