It’s Madness that We Don’t Pay College Athletes

Why I want college players to get money—and learn how to use it

This piece ran on The Player’s Tribune today—but I wanted to make sure my subscribers would have it in their inboxes, too.

Can you imagine what it’s like to be on ESPN playing North Carolina — without $5 to your name?

Can you imagine what it’s like to generate millions in revenue for your school — without being able to buy a hot meal off campus?

Can you imagine what it’s like to be a few months from being able to take care of your family — but knowing that if you twist your leg at the wrong angle, you could lose it all?

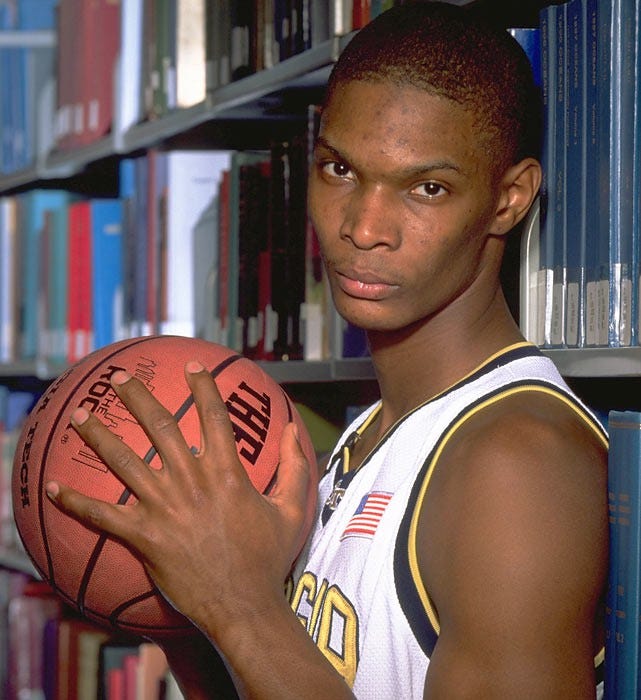

I was 18 when I got to Georgia Tech ... and, suddenly, I became a little more famous and way more broke. In high school, I was allowed to make a few bucks here and there. In college, if I accepted a free jacket because I was cold, my school and my teammates would suffer the consequences.

That’s how college basketball works. It weighs on you.

I still remember trying to figure out how to get groceries when we didn’t have the money to buy them, or when we didn’t have a car we could use to get to the store. I remember feeling hype when the program would buy us Papa John’s for our home games — because it was better than the mystery meat that seven-foot prospects sustained ourselves on in the cafeteria. I remember walking a mile or so back to campus one night after a women’s game with my roommate and teammate, Jarrett Jack. It was my first winter in Atlanta, and we had just missed the school shuttle, the Stinger, because it stopped running around 9:30. Without enough in our bank accounts to pay for a cab to drive us that cold-ass mile back to the dorms, we both lost it. I remember Jarrett throwing up his hands and yelling in frustration, “This is not what college is supposed to be about!”

The NCAA makes more than a billion dollars a year, hundreds of millions of which come from March Madness alone. Television, tickets, food, drinks, jerseys ... they’re making money from dozens of places at once. Meanwhile, the players responsible for the product are not allowed to profit. And don’t even get me started on the women’s side, which is even more skewed against the athletes. Not only are women’s basketball players unable to profit from their incredible contributions to the college game — they’re still having to fight for the most basic levels of equality in terms of treatment, coverage and respect.

And yet even with all of the backlash, all of the voices that have spoken up in the years since I left Georgia Tech — even with a respiratory virus spreading around the world that’s capable of collapsing the lungs of top prospects — basically nothing has changed. Why? Because the NCAA is a business, and they’re not going to change until there’s enough pressure on them that they have no other choice.

Don’t get me wrong: I know that sports depend on capitalism — so I don’t blame the NCAA for trying to profit. But it’s also true that their business isn’t an example of free market economics; it’s an example of a monopoly, old-fashioned exploitation dressed up in terms like amateurism. I believe that instead of punishing a student-athlete for accepting a free coat, the NCAA would be much better off thinking about how to make sure they’re not cold anymore.

So, that’s the first problem with the way college athletes are treated: They aren’t paid what they are worth. Then there’s the second issue: They aren’t prepared for what’s next. Yes, there are cases where rookies dominate on the court in the pros from Day One. But off the court? Man, nobody is ready for what’s about to hit them.

These aren’t necessarily the kinds of things you pick up in a lecture hall or a lab. I’m talking about life skills: how to carry yourself, how to dodge traps, how to know when someone wants to get close to you for the wrong reasons. If you’re playing ball in a big city like Atlanta, and you know you’re going to be a top pick because you refresh NBADraft.net every day, trust me: Other people know, too. And they’re gonna hustle you, squeezing as much out of you as they can, before you know any better.

If you’re lucky — like I was — you get a little bit smarter over time. I started college as a naive teenager, shielded from the truth of what it meant to be the “next big thing.” But along the way, I managed to gather lessons from people around me, people who took it upon themselves to tell me to think about how I would spend and save the money I might end up getting, and how I should shape the career I might end up having. But it took years and dedication to find those people and learn those lessons. And let’s be real: I’m still learning.

That’s how it is for today’s prospects, too. Around two decades after I left college, players at the collegiate level still don’t receive any kind of business education as part of their curriculums — you have to seek it out. In many cases, by the time you get to the League, you haven’t learned enough about how to handle things off the court.

I was 19 years old when the Raptors took me with the fourth pick in the 2003 draft. Even though I knew enough to be a little cautious, I still knew basically nothing about money. It seems like people assume you gain that knowledge the minute you sign your first pro contract. Maybe breaking down the timeline will make clear why that isn’t the case.

May 2003 was my last month of college. By July, I was a Raptor. After the draft, you head to Summer League. The team monitors your workouts for the whole summer to make sure you’re staying in shape. Then they ship you out to Jersey for a three-day Rookie Transition Program, where they try to teach you lessons about what to do and not do with money, as well as other life skills that take years to learn — and they try to fit it all into just a few hours of lectures. So as I was picking up and refining skills in practices and scrimmages, I was flying blind in a few other areas: what to eat, who to avoid, and how to take care of myself in general. There’s just basic stuff you don’t know, stuff you can’t master in a three-day lecture that you don’t even want to attend.

They’re gonna hustle you, squeezing as much out of you as they can, before you know any better.

- Chris Bosh

Early on in my career, I remember a friend asking me: “Can you believe there are professional athletes who don’t have any bottled water in their house?” I didn’t get why he didn’t get it. Of course kids coming up to the pros wouldn’t know to do that. If you’ve never had bottled water in your house before, what’s going to make you turn around and get some just because you have the money? Or start eating healthy food, for that matter? There weren’t exactly many healthy options for food in the inner city of South Dallas when I was growing up.

Every time there’s news about a young athlete — or even an older one — going broke, the refrain is the same: How? To that, I say: If you don’t know anything about money, it’s pretty damn easy to lose it. Even if you know a lot about it, it’s easy to lose. Hell, I’m still figuring it out. But you don’t become an expert on money just by having some.

The system is built on the assumption that a million dollars comes with savvy and smarts, too. But that’s not the case. It does, however, come with a whole world of baggage — baggage your young mind has no idea how to carry.

That’s why I’m not only for paying young athletes, but for educating them as well.

And it’s why I think it’s so important that we start taking a serious look at alternatives to the NCAA’s way of doing things.

In recent years, we’ve seen players successfully take other paths to the NBA: whether it’s going straight to the G League, like Isaiah Todd or Jalen Green; or playing professionally in another country, like LaMelo Ball; or joining Overtime Elite, the league that was recently created for top high school prospects — that will not just pay them, but also provide them with classes on everything from financial literacy, to media training, to social justice.

People are experimenting. They’re opening up their minds.

And when that happens? It’s the athletes who benefit. They will be better players, they will be better professionals and they will be better role models.

The game will be in a better place, too.

Everyone wins.

So what are we waiting for?